People are made in the image of a trinitarian God and we are, therefore, designed to be in relationships. We become incomplete when we’re in a state of isolation: in a basic sense, it’s unnatural because of human nature itself. People need community. And we become more thoughtful when we keep company with others who help us probe our own beliefs and habits and actions more deeply, and more graciously.

Yet many aspects of modern American life make it increasingly easy for people to become isolated. We hide behind social media avatars, we forsake the fellowship of church to watch a sermon video instead, we find newsfeeds that are echo chambers, and we eat meals as if the experience of mealing is a commodity, just like our frozen pizza, or packaged burgers.

The thought of it all can be overwhelming. We face a tidal wave of bad news, it seems. The statistics on teen suicide and the “atomization” of families and the fraying of divided communities and friendships (even households) is – or ought to be – perplexing to even the most optimistic of optimists.

But faint ye not.

Christ taught that the smallest of seeds, like a mustard seed, can yield the greatest of things in relation to His kingdom. In their great little book, The Simplest Way to Change the World, authors Brandon Clements and Dutin Willis reference this teaching to offer an important point for all of us:

In the same way, the ‘smallest’ things in our lives — ordinary days and meals and homes — can have a much larger impact than we’d ever imagine when harnessed with gospel intentionality.

We experienced something of The Mustard Seed principle this month, when 20 people ranging in age from 24 to 84 gathered for a monthly meeting of The Junto Society.

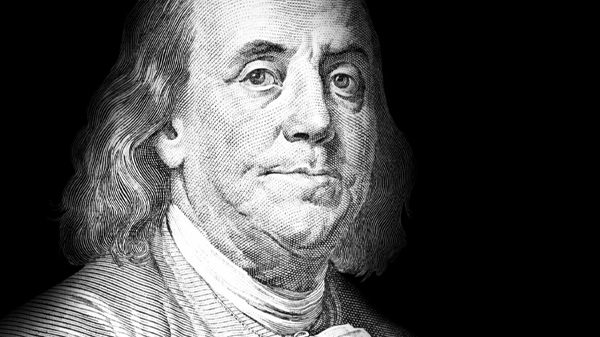

The word “junto” means “together” or “near to” or “along with.” Using the name and general Rules of Order adopted by Ben Franklin’s Junto Society in the late 1700’s, and modeling the spirit of The Clapham Circles formed by William Wilberforce in England at the same time, these gatherings have been hosted at the Homestead since 2000.

Each convening of The Junto Society features a moderated discussion related to propositions brought by the participants who come to the Table. Those participants are reminded of Franklin’s framing principles for constructive conversation, including The Devil’s Rule (which encourages people to take the “devil’s advocate position” without announcing it to discourage ad hominem reactions and “to encourage more light,” as Franklin put it, “and less heat”).

As with the original Junto Society meetings, the propositions must relate to one of the five topical categories selected by Franklin:

…history, culture, political economy, philosophy, and the theology behind it all.

Punctuated by courses of the evening’s community meal, the 15-minute “conversation rounds” invite people to better form their ideas and opinions, and to connect a 360° ideation experience opportunities to advance personal improvement and the common good.

The Junto Society is an eclectic gathering by design, including people of diverse backgrounds and professions and views of the world. New people are part of each gathering, to help shuffle the proverbial deck. I’ve not once experienced a single Junto discussion in 23 years (!) that did not engage opposing points of view, and help inform or change my own.

This month’s propositions engaged participants in all five categories. I was reminded that sometimes the topics are surprising. This week, for example, one proposition was this:

The best colors in God’s world are blues, because blue is calming in all its hues.

Sometimes the topics are very practical. This week one proposition was this (a quote from Samuel Clemens that takes unexpected turns, and perhaps offers a satire inside a satire):

Never put off ‘til tomorrow what may be done the day after tomorrow just as well.

Sometimes the topics are very tangled and knotty, like this proposition (a quote from Golda Meir, Israel’s Prime Minister 50 years ago, which was connected to current news and the many threads of soulful contemplation connected to it):

We can forgive you for killing our children. We cannot forgive you for forcing us to kill your children.

One proposition promoted the relatively recent recognition of Indigenous Peoples’ Day in conjunction with Columbus Day. By the time the conversation was through, I’ve personally never been clearer about why Columbus Day matters (“reflecting one part of our story and identity as a people,” “marking Western Civilization moving Westward,” etc.). AND I’ve never been clearer about why it matters to honor the indigenous people who made this their home before the New World Settlers came (“they are a part of our story, too,” “Native Americans reflect ideals that shaped our own national character,” etc.).

Then came the follow-on discussion. Should we refuse to celebrate Columbus – and the ideals he embodied in exploration, perseverance, faith and invention – because he did not always act justly or wisely? The case was clearly made that if we took that position then we could likewise not support Indigenous Peoples Day, because a good many of them practiced (with other Indigenous Peoples) the very same deeds of enslavement and manslaughter that makes Columbus persona non grata in certain circles today.

The fire was blazing, and the food and drinks were a delight. But to be in company with others, to hear the laughter resonating in the Hall and then to have it become so quiet that you could hear the sizzling wood, to have my views softened and hardened and to gain some new resolve: all of it reminded me to press on in “the ordinary days and meals and homes” and believe that some small seeds are scattered for the sake of things enduring – things beautiful, good and true!

May the mustard tree grow, And may the birds of the air come and lodge in its branches. (Matthew 13:31-32)

Make sharing easy!

Recent Comments