“I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived. I did not wish to live what was not life, living is so dear; nor did I wish to practice resignation, unless it was quite necessary. I wanted to live deep and suck out all the marrow of life, to live so sturdily and Spartan-like as to put to rout all that was not life, to cut a broad swath and shave close, to drive life into a corner, and reduce it to its lowest terms, and, if it proved to be mean, why then to get the whole and genuine meanness of it, and publish its meanness to the world; or if it were sublime, to know it by experience, and be able to give a true account of it in my next excursion.”

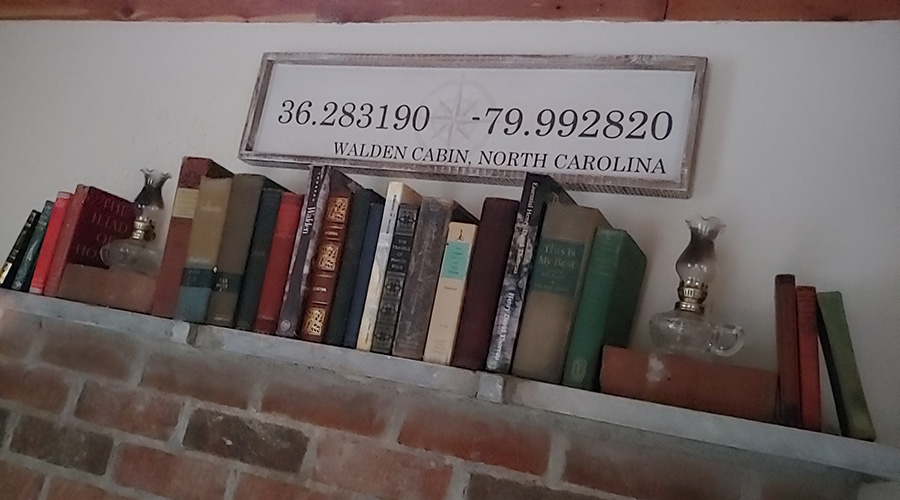

So wrote Henry David Thoreau, giving explanation as to why he went to the woods to live for about two years in a cabin he built near Walden Pond, in Massachusetts. In his book called Walden: Or, Life in the Woods, he chronicles his time there. It’s not easy to read, but it offers pearls of insight for the patient plodder.

The original cabin no longer exists, though its replica (based on period sketches and Thoreau’s own detailed descriptions) is visited each year by about a half million people from all around the world. It is iconic: a symbol of what it is to experience nature, and to contemplate and consider the transcendent things that it evokes. Too many conveniences and distractions, Thoreau believed, can “take the life out of life.” He wanted to simplify his life for a season, to be forced to contemplate things he otherwise might not, and to consider how it might re-make him.

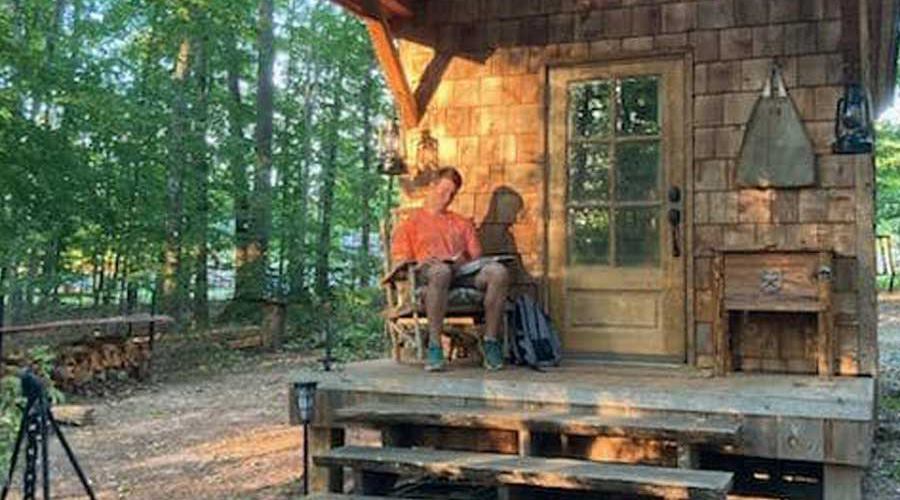

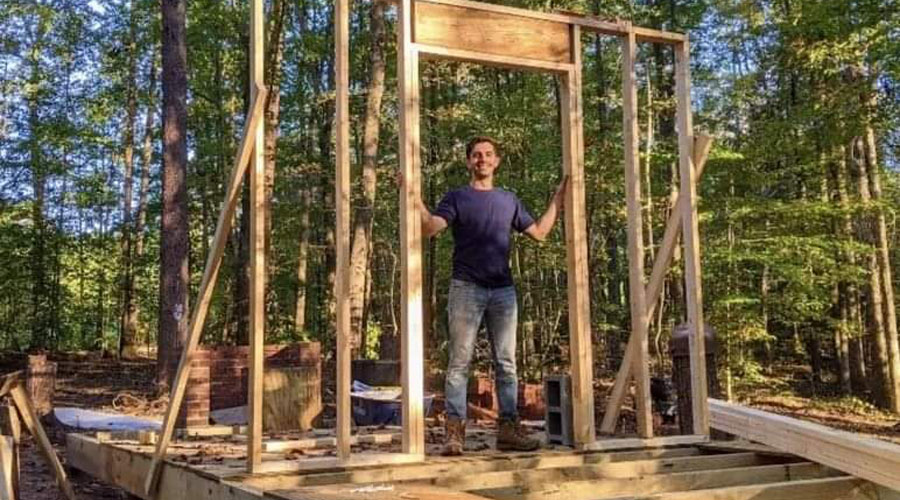

We went to the woods, in July of last year, because we wanted to create a replica of Thoreau’s cabin at Walden Pond to help others experience the same. The project was initiated by a long-time family friend, and sustained by our “builder-in-residence,” John Mark Van Eerden – with help and support from his family and friends. We created a Gantt Chart to outline our intended progress, week by week, and surmised we would have it open for Homestead guests by Thanksgiving (of 2020).

We used mostly materials from the area (including cedar, oak, poplar and pine harvested from our land and from nearby forests). We also used re-cycled supplies, as well as remnants from local building sites, to replicate Thoreau’s experience. A friend even worked with a blacksmith to replicate the nails of the period. We did not use Thoreau’s tools, however. We used modern tools – and marveled often at how Thoreau or anyone built what they built with the tools they used back in 1845!

We sought to honor the principles of Thoreau’s cabin design and experience, but allowed ourselves to make amendments according to what we called “The Third Year Rule” (these were changes we felt Thoreau might make if he had opted to stay a third year). It served as our exceptions clause. For example, we created a root cellar accessible from inside the cabin that can keep food and drinks cold for days, with a single bag or block of ice. We also added (with great pains) the garret loft and made it suitable for a king-sized mattress, with small windows that open on either side of the fireplace to welcome a gentle evening breeze.

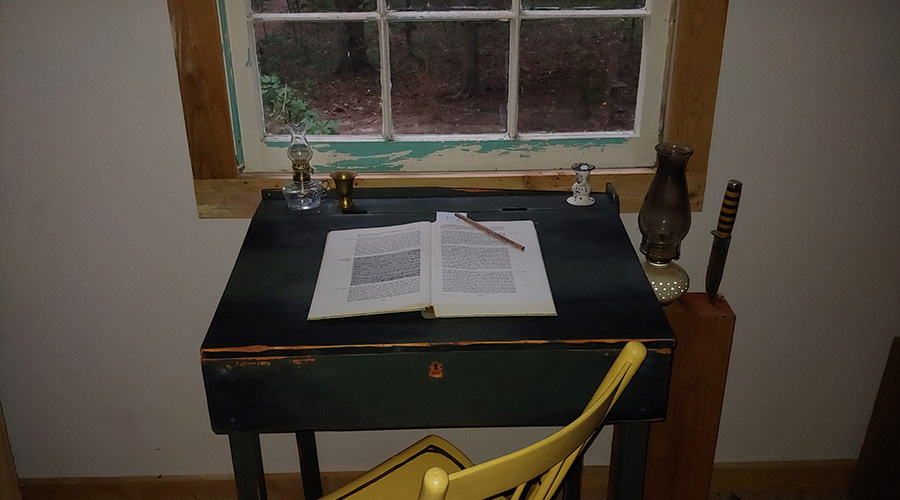

We did our very best to pay careful attention to details. We curated books that he had in his collection, replica pencils from the Thoreau Pencil Co., and ceramic, wooden and iron cookware from the 19th century suitable for use on the open fire or the wood burning stove. We located a kindling box and fireplace grate from the period. A friend created a near exact replica of his famous desk, and a masterfully-designed cedar bed. Another built the cedar chest for the end of the bed, which also serves as a table.

Yet another friend created the famous yellow chair that Thoreau loved, including the intricate painting that makes it so distinctive. This we supplemented with two other signature chairs from the period:

“I had three chairs in my house. One for solitude, two for friendship, three for society.”

It all has been a labor of love. As we neared completion, we framed into the wall to the left of the fireplace Thoreau’s explanation of why he went to the woods. To the right, we framed his summary of what he learned from his time there.

“I learned this, at least, by my experiment: that if one advances confidently in the direction of his dreams, and endeavors to live the life which he has imagined, he will meet with a success unexpected in common hours.”

These quotes stir us each time we read them. They give examples of the gold to be mined in the writings of Thoreau. Some have well noted, however, that Thoreau would have benefited from less focus on himself, and that his proclivities toward being a “loner” sometimes did his soul more harm than good. So it should be said that we don’t hold him out as a model for exemplary character (or friendship, or society, for that matter — much less for his spiritual depth). In this regard, Thoreau’s modern critics have a point.

But they also often miss what we think are his larger contributions. Those contributions are what make Walden Cabin iconic: the importance of adventure, of tests in self-reliance, of solitude, of economy and thrift, and of the kind of observation that leads to wonderment. Thoreau’s book became an American classic in part because it touched upon American ideals that were especially important in the early part of our history.

He is iconic in part because he is ironic. While he was wide-eyed in wonderment, he was also a leader of the minimalist movement. In this regard he’s inspired spirited frontiersmen in pursuit of the American Dream, but he’s also inspired remote workers who live off the grid in tiny homes.

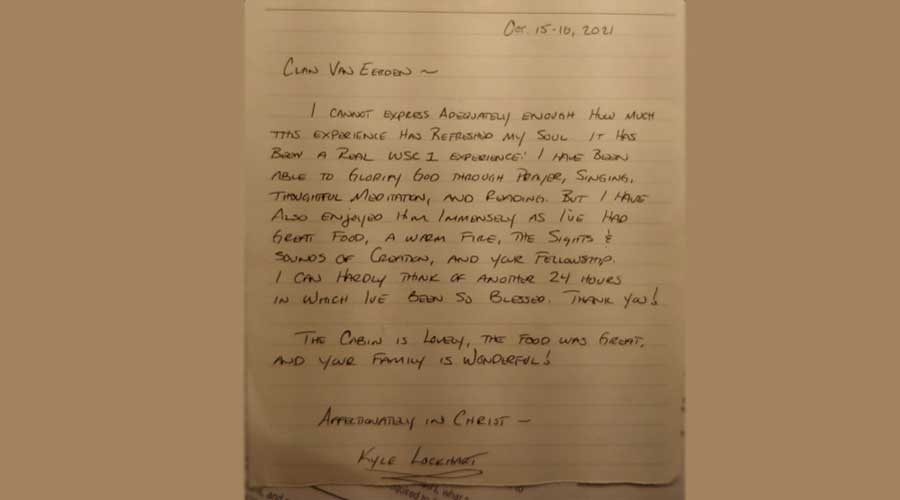

Our prayer is that the Homestead’s Walden Cabin will be a place for these ideals to flourish in a very different generation, and in a very different way — prompting people to turn inward in order to turn upward and outward with more vigor. This is the essence of what early American settlers referred to as the Magnalia Dei: being awakened to the wonders of God revealed in the things that He has made.

Indeed, Thoreau was right when he wrote that most people, in his experience, “have somewhat hastily concluded that it is the chief end of man here to ‘glorify God and enjoy him forever.’” We asked ourselves what it would be for us to instead consider that deeply, and without haste? And so, as you enter in and go out of the cabin, thanks to a mentor who encouraged it, you will pass under the inscription: TGBTGGTHHD.

To God Be The Glory, Great Things He Has Done!

We have consecrated this cabin as a place that will renew the imagination of the souls who visit it – through prayer, through writing, through relationships restored and renewed, through simpleness and minimalism and uncluttered contemplation that leaves to wonder.

So it is with great joy and expectation, at the end of a year-long labor of love, that we invite you to make a reservation to spend a night or more at our Walden Cabin!

P.S. When I went to the woods to take the picture for this post, I went to another place nearby the cabin, to cut some wood, and was stung by a yellow jacket that found its way into my shirt. It stung me three times before I was done with it. I got “the whole and genuine meanness of it.”

P.S.S. It is worth noting that if a man’s error or selfish proclivities prevented us from gaining benefit from them, we would learn nothing from the likes of George Washington, Hemingway, or MLK.

“Live deliberately” – sage advice for a new year.